Across the United Kingdom, the rituals of death are shaped by centuries of tradition, religious belief, and evolving cultural values. Some trace their roots to medieval parish life; others were formalised in Victorian times, while many are now being reimagined to suit the personal and celebratory approach of the modern era. From the solemn toll of half-muffled bells to the sharing of food after burial, each act reflects both a respect for the departed and the needs of the living.

Most British funerals follow one of two paths - burial or cremation. Burials still carry a deeply symbolic gesture: mourners scatter a handful of earth over the coffin as it is lowered, sometimes adding flowers or small keepsakes. While cremation now accounts for the majority of funerals, the act of returning the body to the ground retains emotional weight.

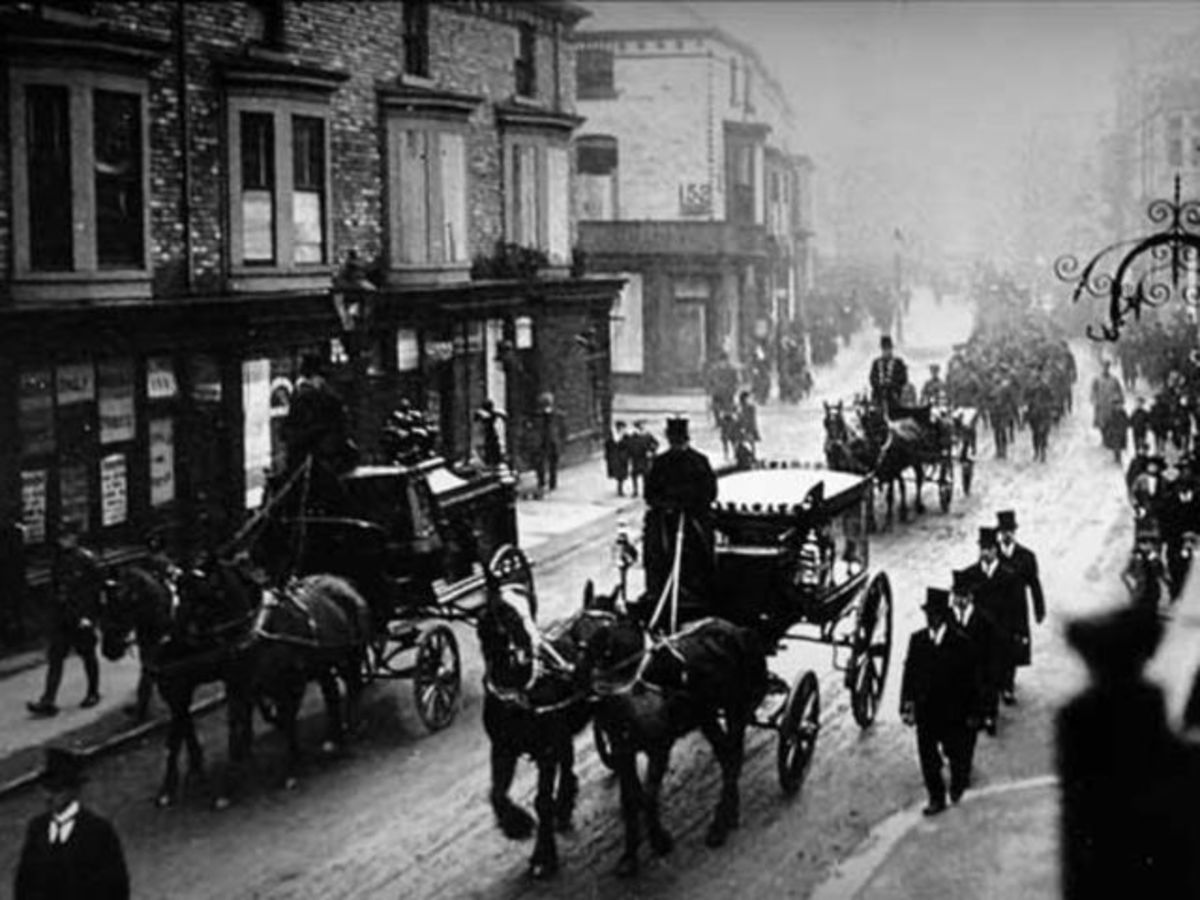

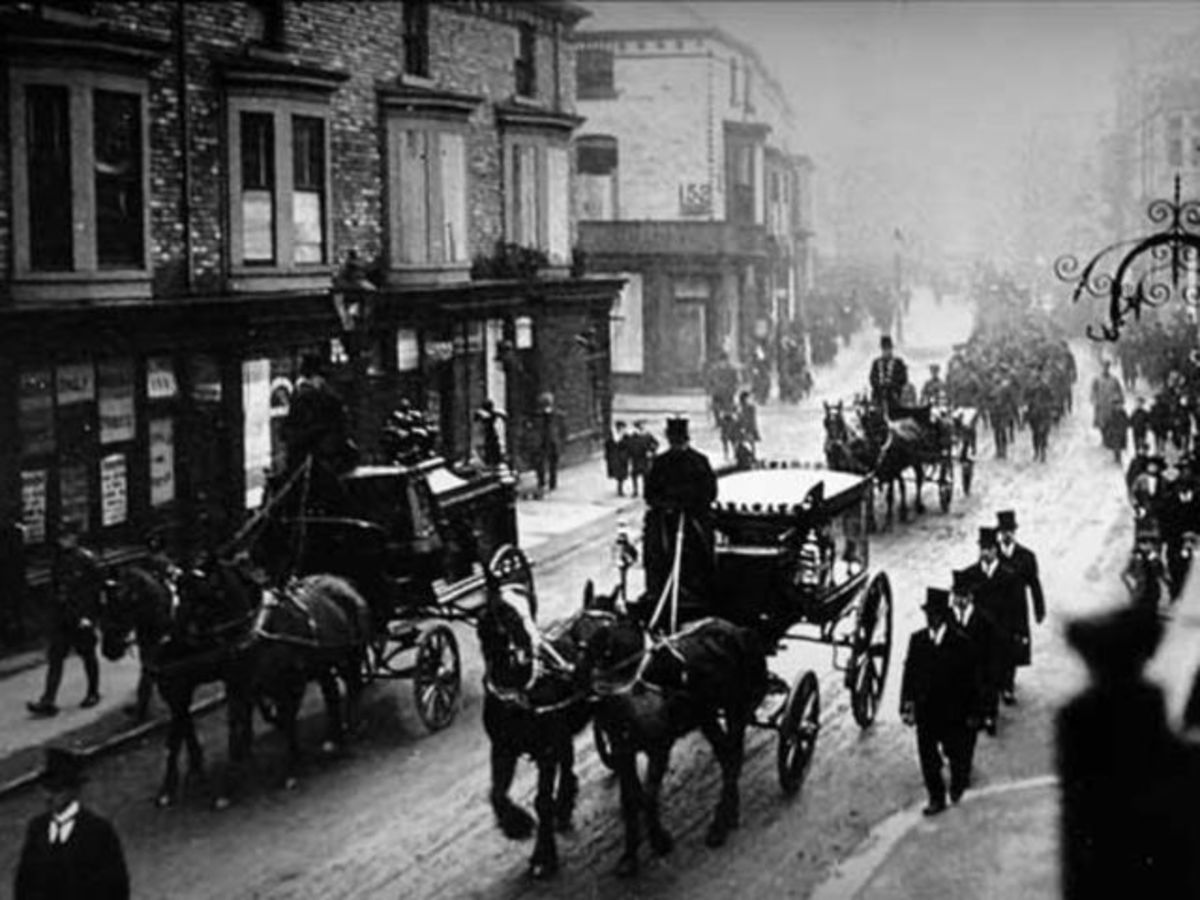

The funeral procession remains a central element. A hearse adorned with flowers leads, followed by vehicles carrying close family. In more traditional settings, the funeral director — known as the funeral conductor — will walk a short distance in front of the hearse, a practice called “paging the cortege.” Dressed in a black morning coat, gloves, and top hat, the conductor sets the dignified pace — a quiet echo of the horse-drawn era, when the undertaker both led and controlled the procession. Originally, this ensured the cortege moved safely through narrow streets while signalling respect to onlookers. Today, it serves as a formal salute to the deceased, giving neighbours and passers-by a visible moment to pause, bow, or remove hats.

This role is distinct from pallbearers (the family or staff who carry the coffin). Historically, Victorian funerals also employed “mutes”—black-clad attendants who walked ahead in silence with staves or scarves as a sign of mourning. The mutes have vanished, but the conductor’s ceremonial walk endures as one of the most recognisable features of a traditional British cortege.

Dress codes have softened, but black or dark clothing is still most common. Many families now request brighter colours to reflect the individuality of the deceased. Flowers, too, carry symbolism — white lilies for purity, roses and carnations for love and remembrance.

After the ceremony, families often host a wake in the home, a hall, or a local pub. This gathering allows friends and relatives to share stories, offer comfort, and honour the life that has ended.

‘No longer mourn for me when I am dead,

Than you should hear the surly, sullen bell,

Give warning to the world that I am fed

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell.’

Today, a single toll may mark a funeral, but in earlier centuries bells told a much richer story. In medieval and early modern England, three distinct tolls were rung, each with its own meaning and purpose.

The origins lie in both faith and folklore. It was believed that evil spirits gathered around the dying, ready to seize the departing soul. To protect the soul’s passage to heaven, the sound of church bells was thought to drive these forces away. The early Church of England even set the practice into law; Canon 67 of 1604 instructed that a bell be tolled at the moment of death, followed by one before burial and one after.

The Passing Bell was rung first, signalling that death was near and summoning the priest to administer the Last Rites.

The Death Knell came immediately after the passing. Slow and deliberate, it carried coded information: two strokes at the start meant a woman had died, three a man. In the north, nine knells for a man, six for a woman, and three for a child were common. Clergy received strokes matching their number of holy orders, and persons of rank were honoured with a concluding peal on all bells. In small parishes, the community could often tell exactly who had died from the sound alone.

Finally, the Lych Bell - sometimes called the Corpse Bell — rang during the funeral procession as it approached the churchyard. This act, known as “ringing home the dead”, marked the last stage of the journey. Of the three tolls, only this one survives in most places today, simplified into the modern funeral toll.

‘Therefore, send not to know

For whom the bell tolls,

It tolls for thee’.

~John Donne’s Meditation XVII, part of his 1624 prose work Devotions upon Emergent Occasions.

Once death was declared, the body was prepared in a ritual known as “laying-out,” traditionally performed by women in the community, often midwives. The body would be washed, dressed in grave clothes, the jaw bound, and the eyes closed with coins. Limbs were straightened and secured with ribbons or cloth. These actions served practical purposes — preventing rigor mortis from altering the features — but also carried symbolic meaning. Closing the eyes was thought to prevent more deaths; washing the body was seen as both a physical cleansing and a form of spiritual preparation.

Today, this intimate work is mostly handled by funeral home staff. In the 1930s, the vast majority of bodies remained at home until burial; now, only a small fraction do, with most moved swiftly to chapels of rest or mortuaries.

Food has long been part of the British funeral tradition. In the 18th and 19th centuries, mourners were offered funeral biscuits — small sweet cakes wrapped in black-bordered paper — sometimes sent to those unable to attend. In rural counties such as Lincolnshire and Cumberland, burial cakes are still made, a survival of the ancient practice of sin-eating, in which bread or cake placed on the coffin was consumed to symbolically absorb the sins of the deceased and grant their soul peace.

“Averil” and the Tradition of Food as Remembrance

In northern England, the funeral repast was sometimes referred to as the avril, arvil, arval or ale cakes, derived from the Old Norse arfr (“inheritance”) and öl (“ale”), meaning a funeral banquet. These meals often featured an arvel cake—a thin, spiced cake given to mourners, wrapped in white paper, and sealed with black wax. Presenting these treats symbolized communal respect and helped reinforce the social bonds shaken by loss. Ale cakes were often washed down with spiced ale or port before the pallbearers carried the body to the burial site

Arvel customs could also include lightly ceremonious elements like “informal inquests” held during the meal, where the legitimacy of the heir was implicitly affirmed

The funeral feast was another important rite. In the early 19th century, mourners returned from the burial to share a cold meal, often centred on a joint of ham. The phrase “we buried him with ham” became shorthand for a proper send-off. While the custom faded after World War II, it is enjoying a quiet revival, with younger generations reframing it as a celebration of life.

Until the late Victorian period, most funerals began and ended at home, with the deceased laid out in the parlour and visited by friends and neighbours. This changed with the rise of the undertaker’s chapel of rest, which offered a private and respectable alternative to the public mortuary - often seen as grim, especially for the poor. With this change, many domestic mourning customs, such as keeping vigil over the body or covering mirrors, began to disappear.

Cremation, once rare, is now the most common form of final disposition. Funerals are often separated from memorial events — the burial or cremation may be private, followed later by a larger celebration of life. This shift has allowed for highly personalised ceremonies, incorporating music, readings, or non-religious elements alongside or instead of traditional liturgy.

Alternative practices have also flourished: woodland burials, biodegradable coffins, scattering ashes at sea or from the air, planting memorial trees, and creating virtual memorial pages online. Public expressions of grief, like the vast floral tributes after the death of Princess Diana in 1997, show how old and new forms of mourning can merge.

Continuity in Change

Continuity in Change

Although the forms have evolved, the heart of Britain’s funeral traditions remains the same — to honour the dead, comfort the living, and mark the passage from one state of being to another. Whether through the soft echo of a half-muffled bell, the symbolic washing of the body, or the sharing of food after burial, these customs affirm that how we say goodbye speaks volumes about how we value life.

Britain’s funeral industry is built not only on tradition but on long lines of family businesses that have cared for the dead for centuries. Some of these firms predate modern embalming, motor hearses, and even the industrial revolution.

The oldest independent funeral directors in the UK, CPJ Field, trace their roots to the late 1600s. Still family-run after more than 300 years and now in its tenth generation, the company’s history runs parallel to the changes in Britain’s burial and mourning customs — from candlelit vigils in the home to today’s personalised memorials.

In York, I W Myers Funeral Directors, founded in 1701, began life as a combined joiner, wheelwright, and undertaker’s workshop - a reminder of the days when the craftsman who made your coffin might also lead the funeral procession. For centuries it operated under the name of I. W. Myers Funeral Directors but in more recent years, it was incorporated into the J G Fielder & Son group.

London’s Leverton & Sons, established in 1789, are today known as funeral directors to the Royal Household, having arranged services for monarchs, statesmen, and national figures. Their long history reflects the ceremonial side of British mourning, where precision and symbolism carry deep meaning.

Others, like S. E. Wilkinson & Son in Northampton (since 1877) or John Heath & Sons in Sheffield (since 1880), stand as local institutions, preserving regional traditions of mourning and remembrance while adapting to contemporary expectations.

These companies are more than businesses — they are keepers of a collective memory, bridging centuries of change in how Britons say goodbye.

Easy Guide to Funeral Homes in Ohio

In Ohio—the “Heart of It All”—families honor their loved ones with a blend of Midwestern practicality and deep community care. From Columbus to Cleveland and Cincinnati, funeral traditions in 2026 reflect a meaningful shift: while many still value the permanence of traditional burial, a growing number are choosing cremation for its flexibility, affordability, and ability to create more personalized memorials.

Easy Guide to Funeral Homes in New York

In New York, funeral planning reflects the state’s fast pace, high costs, and rich cultural diversity. By 2026, families across the Empire State are increasingly balancing long-standing traditions with practical concerns like limited cemetery space, environmental impact, and financial accessibility. From New York City’s dense boroughs to upstate communities, more New Yorkers are embracing flexible, personalized memorial options that honor both legacy and modern realities.

Easy Guide to Funeral Homes in North Carolina

In North Carolina, saying goodbye blends tradition with modern flexibility. While burials remain meaningful, cremation is growing, especially in urban areas, offering personalized memorials and lower costs. Families choose from urns, keepsakes, or scenic tributes, balancing emotional, financial, and environmental considerations. Understanding 2026 trends helps honor loved ones with dignity and lasting care.

Easy Guide to Funeral Homes in Maryland

In Maryland, funeral traditions are shaped by a balance of historic reverence and modern innovation. As of 2026, families across the state are increasingly embracing personalized, environmentally conscious memorials that reflect both practical realities and artistic expression. From urban centers to coastal communities, Marylanders are redefining remembrance in ways that honor legacy, dignity, and evolving values.

Easy Guide to Funeral Homes in Pennsylvania

In Pennsylvania—the Keystone State—the funeral landscape in 2026 reflects a striking balance between colonial-era tradition and modern, consumer-driven change. From Philadelphia to Pittsburgh and the quiet stretches of Amish Country, families are increasingly weighing heritage against flexibility. While traditional burial remains deeply valued for its sense of historical continuity, cremation—now chosen by approximately 56% of residents—offers affordability, personalization, and the option for more contemporary Celebration of Life gatherings.

Share:

Shamanism and the Journey Beyond: Soul-Guiding Rites in Korea and China

How to Choose the Perfect Urn for Your Loved One’s Ashes